All code shown in this article is available in a Github repository.

What about Microservices?

Before we talk about monoliths, we should spend some time thinking about when and why a microservices architecture makes sense.

- There is the single-responsibility principle, which states that “every class in a computer program should have responsibility for a single part of that program’s functionality, which it should encapsulate”. A microservices architecture brings this to a new level, where each service should have a single responsibility. This makes testing and changing a single service much easier since it is very clear what the service is doing.

- You have multiple teams, and each team can work and release independently on their part of the system. Maybe even using different programming languages.

- You can scale independently because some parts of the application will have more load than others.

- The deployment target is a well-known and defined area that is under your control.

- The environment where your services are running is not resource-constraint.

This is by far not a complete list, but just some examples. And while microservices help if you can answer the mentioned points with “yes”, there are also drawbacks, like:

- Higher human communication overhead: The teams/people working on different services need to communicate a lot to ensure that changes in one service will not break other services.

- Documentation overhead: Each service needs to have up-to-date documentation that you can hand over to others when they have to use the service.

- Different tech-stacks: If your microservices architecture uses different tech-stacks for each service, there might be a business risk to find appropriate developers for that tech-stack.

- Proper fault handling: Every service needs to have proper fault handling. In a microservices architecture, there are more moving parts, and every service should be able to react appropriately if another service is not available.

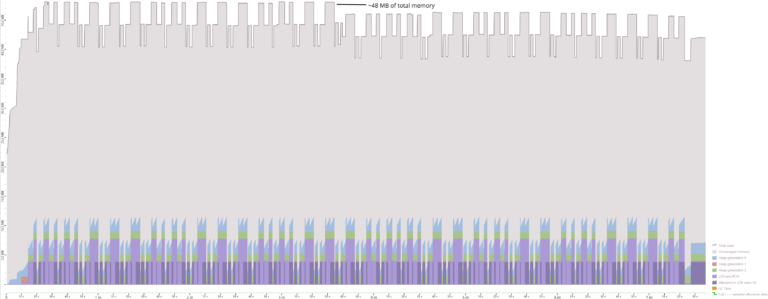

- Higher resource costs: Each service will load its runtime environment. This increases the usage of memory and CPU. Data duplication might occur and also increases the overhead.

Overall, a microservices architecture might be way more complex than what you need or want.

What about a Monolithic Architecture?

So, what is the alternative if you can not or do not want to use a microservices architecture? A monolith?! But isn’t a monolith… old… and… bad? Highly coupled spaghetti code?

Well, yes and no! While in the past, a lot of monolithic applications were highly coupled and sometimes just a “mess of spaghetti code”, times have changed. Developers did not have the tools and frameworks to easily write decoupled code. Especially in the old ASP.NET (WebForms) era…

- there was no dependency injection

- the runtime and framework itself was highly coupled

- there were no libraries helping us implementing best practices design patterns

While monoliths are more coupled, with years of Clean Code movement, new frameworks, strict coding guidelines, and code reviews, we can reduce the coupling and are able to create a well-defined monolithic application.

What is a Modular Monolith?

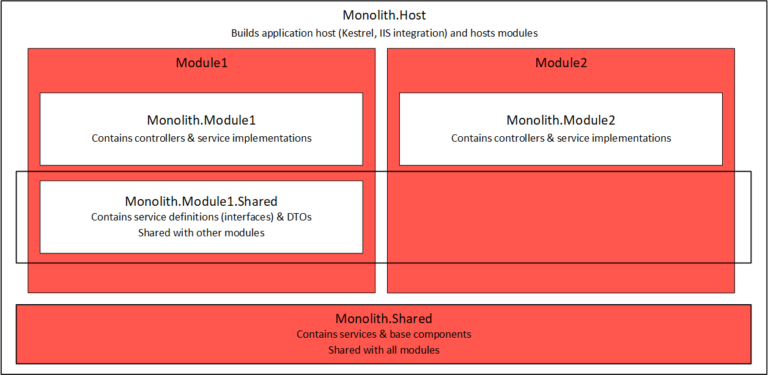

So, what is a modular monolith? A modular monolith is still a monolith, but the term monolith refers more to the hosting/runtime model. All services/parts live in the same solution (not in the same project!), are running in the same process, and are therefore deployed at the same time. But, each service/part is located in its own module (.NET project) and is therefore decoupled from other modules. Let’s take a look at this example architecture:

In the outer area, we have the Monolith.Host, which is the assembly that hosts all modules. In ASP.NET Core, this will be the project that builds the application host (Kestrel, IIS integration) and hosts the modules. Module1 and Module2 are logical views of different functional modules. Each module consists of one or more assemblies that contain the logic of a module. E.g. Monolith.Module1 and Monolith.Module2 each have the ASP.NET Core controllers provided by the respective module. Ideally, all classes in a module should be internal to prevent accidental usage in other modules.

If a module needs to share logic with other modules, it should provide interfaces in a Shared assembly. This shared assembly can be referenced and used by other modules. At the bottom, we have a Monolith.Shared library that contains base components available to all modules.

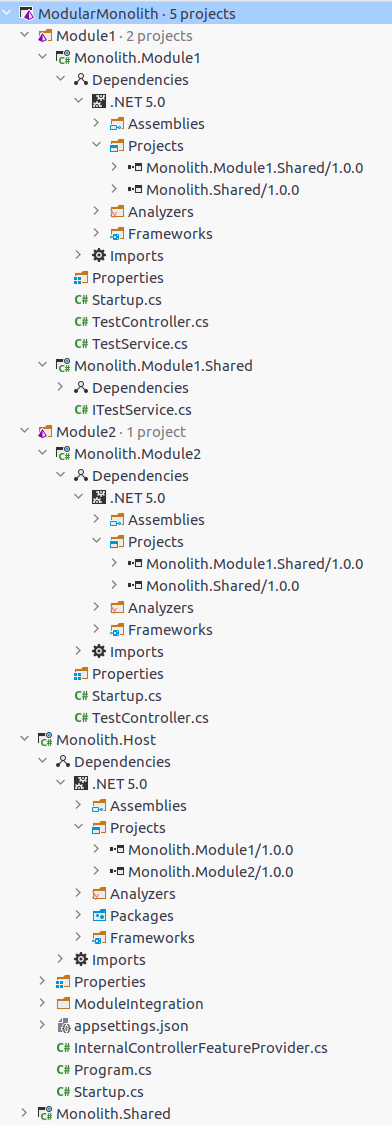

This example solution contains two modules, Monolith.Module1 and Monolith.Module2. For Module1, a shared service (ITestService) is defined in its own shared-project (Monolith.Module1.Shared), but its implementation (TestService) is actually in Monolith.Module1.

Customizing ASP.NET Core

With ASP.NET Core, we have a good starting point when it comes to modular monoliths – for example, built-in dependency injection. But we still need to extend ASP.NET Core to fully have a modular monolith. Fortunately, this is possible because ASP.NET Core itself is modular and extensible.

Make Everything Internal

In a modular monolith, it is good practice to make everything inside a module internal. While technically this is not necessary, it will prevent accidental usage of components outside the module. This can happen e.g. with auto-imports functionality of Visual Studio extensions or ReSharper. It also reduces pollution in IntelliSense and establishes a clear intent of what is public usable. Only interfaces defined in the Shared project should be public. If access to the internal components is needed in a test-project, the InternalsVisibleToAttribute can be used.

Internal API Controllers

Out of the box, ASP.NET Core expects you to make your controllers public. internal controllers will not be detected and therefore are not available via routes. We can extend ASP.NET Core to use internal controllers by implementing and registering a custom ControllerFeatureProvider. The ControllerFeatureProvider will be called by ASP.NET Core MVC to determine if the given type is a controller or not.

public class InternalControllerFeatureProvider : ControllerFeatureProvider

{

protected override bool IsController(TypeInfo typeInfo)

{

var isCustomController = !typeInfo.IsAbstract

&& typeof(ControllerBase).IsAssignableFrom(typeInfo)

&& IsInternal(typeInfo);

return isCustomController || base.IsController(typeInfo);

bool IsInternal(TypeInfo t) =>

!t.IsVisible

&& !t.IsPublic

&& t.IsNotPublic

&& !t.IsNested

&& !t.IsNestedPublic

&& !t.IsNestedFamily

&& !t.IsNestedPrivate

&& !t.IsNestedAssembly

&& !t.IsNestedFamORAssem

&& !t.IsNestedFamANDAssem;

}

}

Controller Auto-Detection

ASP.NET Core scans all assemblies and automatically makes all found controllers available. While we can not disable this feature, we can clear out the found controllers and register our own controllers “by hand”. We need this for custom routing to our modules.

services.AddControllers().ConfigureApplicationPartManager(manager =>

{

// Clear all auto-detected controllers.

manager.ApplicationParts.Clear();

// Add feature provider to allow "internal" controller

manager.FeatureProviders.Add(new InternalControllerFeatureProvider());

});

Routing to Module Controllers

To prevent name clashes between controllers in different modules, we should prefix all routes to modules. E.g.

[Route("[module]/[controller]")]

internal class TestController : Controller

Next, we need to implement a custom IActionModelConvention which adds the module prefix to the route values. ActionModelConventions are invoked for every action on startup and allow to customize e.g. routing to the action.

public class ModuleRoutingConvention : IActionModelConvention

{

private readonly IEnumerable<Module> _modules;

public ModuleRoutingConvention(IEnumerable<Module> modules)

{

_modules = modules;

}

public void Apply(ActionModel action)

{

var assembly = action.Controller.ControllerType.Assembly

var module = _modules

.FirstOrDefault(m => m.Assembly == assembly);

if (module == null)

{

return;

}

action.RouteValues.Add("module", module.RoutePrefix);

}

}

Startup per Module

To allow registration of custom services in a module, we should provide a startup file per module. This can be done by defining an IStartup interface that can be implemented in a module.

public interface IStartup

{

void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services);

void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env);

}

An example implementation of IStartup might look like this.

public class Startup : IStartup

{

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddSingleton<ITestService, TestService>();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

endpoints.MapGet("/TestEndpoint",

async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello World");

}).RequireAuthorization()

);

}

}

Module Registration

The final step is to put everything together and create an IServiceCollection extension to register modules. This extension will also invoke the startup of the module.

public static IServiceCollection AddModule<TStartup>(this IServiceCollection services, string routePrefix)

where TStartup : IStartup, new()

{

// Register assembly in MVC so it can find controllers of the module

services.AddControllers().ConfigureApplicationPartManager(manager =>

manager.ApplicationParts.Add(new AssemblyPart(typeof(TStartup).Assembly)));

var startup = new TStartup();

startup.ConfigureServices(services);

services.AddSingleton(new Module(routePrefix, startup));

return services;

}

This extension and all other parts needed will be invoked in the Startup of the host, e.g.

public class Startup

{

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddControllers().ConfigureApplicationPartManager(manager =>

{

// Clear all auto-detected controllers.

manager.ApplicationParts.Clear();

// Add feature provider to allow "internal" controller

manager.FeatureProviders.Add(new InternalControllerFeatureProvider());

});

// Register a convention allowing us to prefix routes to modules.

services.AddTransient<

IPostConfigureOptions<MvcOptions>,

ModuleRoutingMvcOptionsPostConfigure>();

// Adds module1 with the route prefix module-1

services.AddModule<Module1.Startup>("module-1");

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

app.UseRouting();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints => { endpoints.MapControllers(); });

// Adds endpoints defined in modules

var modules = app

.ApplicationServices

.GetRequiredService<IEnumerable<Module>>();

foreach (var module in modules)

{

app.Map($"/{module.RoutePrefix}", builder =>

{

builder.UseRouting();

module.Startup.Configure(builder, env);

});

}

}

}

Conclusion

Even with the history of monoliths and the current ongoing hype of microservices, it is possible to build clean monoliths with .NET and ASP.NET Core. It is not always necessary to create microservices, and especially when you need to build something fast, a modular monolith might be a good start. With proper decoupling, the modular monolith might be split into separate microservices later on.

All code shown in this article is available in a Github repository.